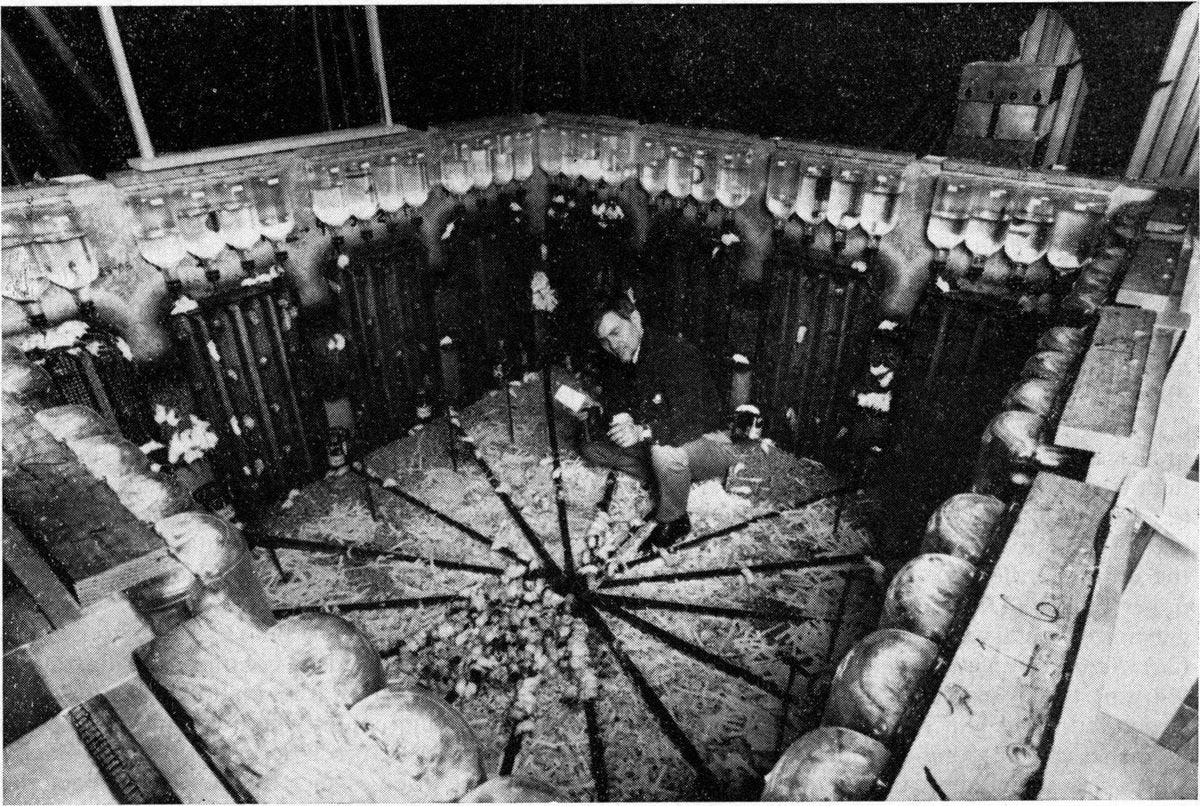

This is hardly scientific, empirical data, but it seems to me that two of the behavioral experiments that have been most popularized in the minds of the general public are Stanley Milgram’s early 1960s studies at Yale intended to measure the willingness of study participants to obey an authority figure who instructed them to give electrical shocks to other people, and John Calhoun’s “Mouse Utopia” experiments, which ran from 1958 to 1972 at the NIMH. In those experiments, Calhoun and his researchers created a series of "rat utopias" – enclosed spaces where rats (and later, mice) were given unlimited food and water, enabling massive population growth, eventually leading to overpopulation and what Calhoun called “behavioral sink,” a collapse in normal rodent behavior.

While the Milgram and Calhoun experiments have become somewhat entrenched in popular culture, with significant policy implications, both experiments have been the subject of critique within the scientific community for methodological and ethical issues. For a variety of reasons, neither study could be performed today by any research institution of standing. Because of those flaws, their impact on popular culture as well as political policy should raise some troubling implications. I decided to see what the Grok AI app had to say about things (no obvious AI hallucinations, but normal caveats apply). My prompts are in bold italic.

Explain the criticism of the famous Milgram experiment

The Milgram Experiment, conducted by Stanley Milgram in the 1960s, is one of the most famous studies in psychology, designed to explore obedience to authority. It involved participants (the "teachers") administering what they believed were electric shocks to a "learner" (a confederate) under the direction of an authority figure (the experimenter). While the study revealed shocking insights into human behavior—showing that many people would obey orders to inflict harm—it has faced significant criticism over the years. Below is an explanation of the key criticisms:

1. Ethical Concerns Deception and Lack of Informed Consent: Participants were misled about the true nature of the experiment. They believed they were administering real electric shocks, which caused significant stress and emotional distress. This deception violated ethical standards, as participants were not fully informed about the study's purpose or procedures. Psychological Harm: Many participants experienced intense stress, guilt, or anxiety during and after the experiment, as they were led to believe they were causing harm to another person. Critics argue that the psychological toll on participants was not adequately addressed or mitigated. Inability to Withdraw: While participants were technically allowed to stop, the experimenter's authoritative prompts (e.g., "You must continue") created pressure that made it difficult for participants to feel they could freely withdraw, undermining the principle of voluntary participation.

2. Methodological Flaws Demand Characteristics: Critics argue that participants may have been responding to subtle cues from the experimenter, leading them to behave in ways they thought were expected rather than reflecting genuine obedience. The artificial lab setting may have amplified this effect. Lack of Ecological Validity: The controlled, artificial environment of the experiment does not necessarily reflect real-world situations. Obedience in a lab under an experimenter's authority may not generalize to complex, real-life scenarios where authority is less clear-cut. Sample Bias: The original study primarily used male participants from a specific demographic (mostly white, middle-class Americans). This limits the generalizability of the findings to other populations, cultures, or contexts.

3. Interpretation and Overgeneralization Oversimplification of Obedience: Critics argue that Milgram's conclusions oversimplify human behavior by focusing on obedience without fully accounting for individual differences, situational factors, or moral reasoning. For example, some participants may have continued due to trust in the experiment's legitimacy rather than blind obedience. Neglect of Dissenters: While the study emphasized the high rates of obedience (e.g., 65% of participants administered the maximum shock), it often downplayed the significant minority who resisted or refused to continue, which could provide insights into factors that promote defiance of unethical authority.

4. Historical and Contextual Misapplication Link to Historical Events: Milgram framed his study as an explanation for atrocities like those committed during the Holocaust, suggesting that ordinary people could commit horrific acts under authority. Critics argue this analogy is overly simplistic, as historical events involve complex social, political, and ideological factors not captured in the experiment. Cultural and Temporal Bias: The experiment was conducted in the 1960s in a specific cultural context (post-World War II America). Critics question whether the results would hold in different cultural or historical settings where attitudes toward authority might differ.

5. Reproducibility and Variations Ethical Barriers to Replication: Due to modern ethical standards, replicating the Milgram experiment in its original form is nearly impossible, making it difficult to verify or challenge the findings. Partial replications or variations (e.g., Burger, 2009) have produced mixed results, raising questions about the robustness of the original conclusions. Influence of Experimenter: The experimenter's behavior (e.g., tone, authority, insistence) played a significant role in eliciting obedience. Critics argue that the results may reflect the specific dynamics of the experimenter's authority rather than a universal tendency to obey.

6. Manipulation of Data and Reporting Selective Reporting: Some critics, such as historian Gina Perry, have pointed out that Milgram may have selectively reported data to emphasize obedience. For instance, unpublished variations of the experiment showed lower obedience rates under certain conditions, which were not as prominently featured in his work. Exaggeration of Results: Milgram's narrative focused heavily on the shocking compliance rates, which some argue overstated the prevalence of blind obedience and downplayed variability in participant responses.

7. Alternative Explanations Social Identity Theory: Some researchers, like Stephen Reicher and Alexander Haslam, suggest that participants' behavior may reflect identification with the experimenter's scientific goals (a sense of "doing good" for science) rather than blind obedience to authority. Engaged Followership: Rather than passively obeying, participants may have actively engaged with the experimenter's requests, believing their actions served a higher purpose, which challenges the traditional interpretation of the study. Broader Impact of Criticism The criticisms of the Milgram Experiment have had a lasting impact on psychology, leading to stricter ethical guidelines for research, such as those outlined by the American Psychological Association (APA). They also sparked debates about the balance between scientific discovery and participant welfare, as well as the complexity of human behavior in response to authority. Despite these critiques, the experiment remains a cornerstone of social psychology, prompting ongoing discussions about obedience, morality, and the ethics of research.

If you'd like me to delve deeper into any specific criticism, analyze related studies, or provide insights from recent discussions (e.g., from X or web sources), let me know!

Compare the flaws in the Milgram experiment with those of John Calhoun's mouse utopia.

The Milgram Experiment (1960s) and John B. Calhoun’s Mouse Utopia experiments (1940s–1970s) are landmark studies in psychology and behavioral science, but both have faced significant criticism for methodological, ethical, and interpretative flaws. Below is a comparison of the flaws in these two experiments, focusing on their ethical issues, methodological limitations, and interpretive challenges, while highlighting similarities and differences.

1. Ethical Concerns

Milgram Experiment Deception and Informed Consent: Participants were misled into believing they were administering real electric shocks, violating informed consent. They were unaware of the study's true purpose (measuring obedience), which caused emotional distress.

Psychological Harm: Participants experienced significant stress, guilt, and anxiety, believing they were harming another person. The lack of adequate debriefing or follow-up care exacerbated this harm.

Coercion to Continue: The experimenter’s authoritative prompts (e.g., “You must continue”) made participants feel pressured to continue, undermining their ability to withdraw freely. Impact: These ethical issues led to stricter guidelines in human research, emphasizing informed consent and participant welfare.

Mouse Utopia (Calhoun’s Experiments) Animal Welfare Concerns: Calhoun’s experiments involved housing mice in overcrowded, resource-abundant environments to study behavioral collapse. Critics argue that the conditions (e.g., extreme crowding, lack of escape) caused undue suffering, raising questions about the ethics of animal research.

Lack of Ethical Oversight: Conducted before modern animal welfare standards (e.g., Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees), the experiments lacked formal ethical review, allowing prolonged distress for the mice.

Manipulation of Environment: The deliberate creation of dystopian conditions (e.g., overcrowding leading to aggression, cannibalism, and social breakdown) was seen as ethically problematic, as it prioritized scientific observation over animal well-being.

Impact: These concerns contributed to the development of ethical guidelines for animal research, such as minimizing harm and justifying experimental conditions. Comparison:

Similarity: Both experiments prioritized scientific inquiry over the well-being of subjects (humans in Milgram, mice in Calhoun), raising ethical questions about harm and consent.

Difference: Milgram’s study involved human participants, making deception and psychological harm central issues, whereas Calhoun’s focused on animals, with ethical concerns centered on animal suffering and lack of welfare standards.

Context: Milgram’s ethical violations directly influenced human research ethics, while Calhoun’s work contributed to animal welfare regulations, reflecting different ethical domains.

2. Methodological Flaws

Milgram Experiment

Demand Characteristics: Participants may have responded to cues from the experimenter, behaving in ways they thought were expected rather than reflecting genuine obedience.

Lack of Ecological Validity: The artificial lab setting (e.g., a controlled shock machine and scripted experimenter) did not mirror real-world authority dynamics, limiting generalizability.

Sample Bias: The study used a narrow demographic (mostly white, middle-class American males), reducing applicability to diverse populations or cultures.

Reproducibility Issues: Modern ethical restrictions prevent exact replication, and partial replications (e.g., Burger, 2009) show varied results, questioning the original findings’ robustness. Mouse Utopia

Artificial Environment: The “utopia” was an unnatural, confined space with unlimited resources but no predators or natural challenges, making it difficult to generalize findings to natural ecosystems or human societies.

Lack of Control Groups: Calhoun’s experiments often lacked rigorous control groups to isolate variables like crowding versus other environmental factors, weakening causal claims.

Small Sample Sizes and Variability: Some trials involved small populations or inconsistent conditions, leading to variability in outcomes that critics argue was not adequately addressed.

Reproducibility Challenges: Replicating the exact conditions of Calhoun’s experiments is difficult due to their complexity and ethical concerns, limiting verification of results. Comparison:

Similarity:

Both studies suffered from artificial settings that limited ecological validity, making it hard to apply findings to real-world contexts (human obedience for Milgram, social behavior for Calhoun).

Difference:

Milgram’s flaws centered on human behavior in a controlled lab, with issues like demand characteristics, while Calhoun’s flaws involved animal behavior in an unnatural environment, with problems like lack of controls and ecological relevance.

Reproducibility:

Both face replication challenges, but Milgram’s are due to ethical restrictions, while Calhoun’s stem from both ethical concerns and the complexity of recreating the experimental conditions.

3. Interpretive and Generalization Issues

Milgram Experiment

Oversimplification: Milgram’s framing of obedience as a universal trait oversimplified complex human behavior, ignoring factors like trust in science or individual moral reasoning.

Historical Misapplication: Linking the results to events like the Holocaust was criticized as reductive, as historical atrocities involve ideological, social, and political factors not captured in the lab.

Neglect of Dissenters: The focus on high obedience rates (65% administered maximum shocks) downplayed participants who resisted, limiting insights into defiance.

Selective Reporting: Critics (e.g., Gina Perry) argue Milgram selectively emphasized high obedience rates, omitting variations where obedience was lower.

Mouse Utopia

Overgeneralization to Humans: Calhoun’s findings, particularly the “behavioral sink” (social collapse due to overcrowding), were often applied to human societies (e.g., urban decay), but critics argue this anthropomorphism ignores human adaptability, culture, and agency.

Ignoring Alternative Factors: The experiments attributed behavioral collapse primarily to crowding, but other factors (e.g., lack of predators, unnatural diets, or confinement stress) were not sufficiently explored.

Sensationalized Conclusions: Calhoun’s dramatic descriptions (e.g., “utopia” turning into dystopia) were criticized for exaggerating findings to draw public attention, potentially skewing scientific interpretation.

Neglect of Resilience: The focus on pathological behaviors (e.g., aggression, withdrawal) overlooked cases where mice adapted or showed resilience, limiting the study’s scope. Comparison:

Similarity: Both studies were criticized for overgeneralizing results—Milgram to human obedience universally, Calhoun to human societies—without accounting for contextual nuances.

Difference: Milgram’s interpretations were tied to specific historical analogies (e.g., Nazi obedience), while Calhoun’s were applied more broadly to societal trends (e.g., urbanization), making his overgeneralizations less historically specific but still speculative.

Focus on Pathology: Both emphasized negative outcomes (obedience to harm in Milgram, social collapse in Calhoun) while underreporting positive or resistant behaviors, skewing their narratives.

4. Broader Contextual and Cultural Critiques

Milgram Experiment

Cultural Bias: Conducted in 1960s America, the study reflected a specific cultural attitude toward authority, which may not apply to other cultures or eras with different power dynamics.

Historical Context: The post-World War II focus on understanding authoritarianism influenced Milgram’s design and interpretation, potentially biasing the study toward obedience findings.

Mouse Utopia

Cultural Projections: Calhoun’s work was influenced by mid-20th-century fears of overpopulation and urban decay, leading to interpretations that reflected these anxieties rather than objective analysis.

Lack of Cross-Species Validation: Applying mouse behavior to humans ignored fundamental differences in cognition, culture, and social structures, a critique rooted in the study’s speculative leap. Comparison:

Similarity: Both studies were shaped by their historical and cultural contexts (post-WWII authoritarianism fears for Milgram, overpopulation anxieties for Calhoun), leading to biased interpretations.

Difference: Milgram’s cultural bias was tied to human authority dynamics, while Calhoun’s was linked to broader societal fears, making his interpretations more speculative due to the human-animal gap.

Summary of Key Similarities and Differences Similarities: Both experiments faced ethical criticism for causing harm (psychological for Milgram’s participants, physical/emotional for Calhoun’s mice). Both suffered from methodological issues like artificial settings and limited generalizability. Both were criticized for oversimplifying complex behaviors and overgeneralizing to broader contexts (human obedience, societal collapse). Both had significant cultural impact but faced challenges in replication due to ethical and practical constraints. Differences: Milgram’s flaws centered on human subjects, raising issues of consent and psychological harm, while Calhoun’s involved animal subjects, focusing on welfare and anthropomorphism. Milgram’s study was more controlled but lacked ecological validity, while Calhoun’s was less controlled and struggled with isolating variables like crowding. Milgram’s interpretations were tied to specific historical events, while Calhoun’s were broader and more speculative, applied to human societal trends.

Conclusion

The Milgram Experiment and Calhoun’s Mouse Utopia both pushed boundaries in understanding behavior but were flawed in ways that reflect their respective domains (human psychology vs. animal behavior). Milgram’s ethical violations and oversimplification of obedience sparked debates about research ethics, while Calhoun’s animal welfare issues and anthropomorphic interpretations raised questions about cross-species generalizations. Both studies remain influential but serve as cautionary tales about the need for ethical rigor, methodological robustness, and careful interpretation in behavioral research.

Would Milgram and Calhoun be accused of scientific fraud if they published their work today?

To determine whether Stanley Milgram and John B. Calhoun would be accused of scientific fraud if they published their work today, we need to clarify what constitutes scientific fraud and evaluate their experiments (the Milgram Obedience Experiment and Calhoun’s Mouse Utopia) against modern standards. Scientific fraud typically involves deliberate falsification, fabrication, or plagiarism—such as manipulating data, inventing results, or misrepresenting findings. Below, I’ll assess whether their work would meet this threshold, considering ethical, methodological, and interpretive issues, and how modern scientific standards would view their studies.

1. Understanding Scientific Fraud Scientific fraud is defined as intentional misconduct, such as:

Fabrication: Making up data or results. Falsification: Manipulating data or results to misrepresent findings. Plagiarism: Copying others’ work without credit. Misrepresentation: Deliberately exaggerating or misstating findings to mislead. Ethical violations or methodological flaws, while serious, do not automatically constitute fraud unless they involve intentional deception. With this in mind, let’s examine each experiment.

2. Milgram Obedience Experiment Overview Milgram’s 1960s experiments explored obedience to authority by having participants (the “teachers”) administer what they believed were electric shocks to a “learner” (a confederate) under an experimenter’s direction. The study revealed high obedience rates but faced ethical and methodological criticism.

Would Milgram Be Accused of Fraud Today?

Ethical Issues: Milgram’s use of deception (misleading participants about the shocks), psychological harm (causing stress and guilt), and coercive pressure (prompts like “You must continue”) would violate modern ethical guidelines (e.g., APA’s Ethical Principles, post-1970s). These are serious ethical breaches but not fraud, as they don’t involve fabricating or falsifying data.

Methodological Concerns: Critics note issues like demand characteristics (participants responding to experimenter cues), sample bias (mostly male, American participants), and lack of ecological validity. These are flaws but not evidence of intentional manipulation.

Data and Reporting Issues: Historian Gina Perry and others have criticized Milgram for selective reporting—emphasizing high obedience rates (e.g., 65% administering maximum shocks) while downplaying variations where obedience was lower. Archival evidence suggests Milgram was aware of inconsistencies (e.g., unpublished conditions with lower obedience) but chose to highlight dramatic results. While this selective emphasis borders on misrepresentation, it’s not clear it rises to deliberate falsification, as the data itself wasn’t fabricated. Modern peer review might flag this as biased reporting but likely not fraud.

Modern Context: If published today, Milgram’s study would likely be rejected by institutional review boards (IRBs) due to ethical violations, preventing publication in reputable journals. However, accusations of fraud would require evidence of intentional data manipulation, which is not strongly supported. Instead, Milgram would face criticism for ethical misconduct and biased interpretation, potentially leading to retractions or sanctions but not necessarily fraud charges. Verdict: Milgram would likely not be accused of scientific fraud but would face severe ethical scrutiny, likely preventing publication. His selective reporting could be criticized as misleading, but it falls short of deliberate fabrication or falsification.

3. Calhoun’s Mouse Utopia Experiments

Overview Calhoun’s experiments (1940s–1970s) studied mouse behavior in overcrowded, resource-abundant environments, observing “behavioral sink” (social collapse, aggression, withdrawal). The findings were often applied to human societal issues like overpopulation.

Would Calhoun Be Accused of Fraud Today?

Ethical Issues: Calhoun’s experiments involved significant animal suffering (e.g., overcrowding leading to aggression, cannibalism, and population collapse). Modern animal welfare standards (e.g., those set by the Animal Welfare Act or IACUC guidelines) would deem these conditions unethical. However, ethical violations in animal research are not equivalent to fraud unless they involve deceit about the study’s conduct or results.

Methodological Concerns: The experiments lacked robust control groups, had small or variable sample sizes, and relied on artificial environments, limiting generalizability. These are methodological weaknesses but not evidence of intentional manipulation.

Interpretive Overreach: Calhoun’s application of mouse behavior to human societies (e.g., urban decay) was criticized as speculative anthropomorphism. His dramatic framing (e.g., “utopia” to dystopia) may have exaggerated findings for impact, but there’s no clear evidence he fabricated data. His interpretations were speculative, but this is a matter of scientific judgment, not fraud.

Data Integrity: There’s no documented evidence that Calhoun falsified or fabricated data. His observations (e.g., behavioral sink) were based on real experiments, though critics argue he overemphasized pathological outcomes while underreporting adaptive behaviors. This selective focus could be seen as biased but not fraudulent unless intentional deceit is proven.

Modern Context: If published today, Calhoun’s work would face rejection by animal ethics committees due to welfare concerns. Journals might criticize his overgeneralizations to humans, but fraud accusations would require evidence of data manipulation, which is not apparent. His work might be scrutinized for sensationalism, but this is distinct from fraud.

Verdict: Calhoun would likely not be accused of scientific fraud but would face ethical and interpretive criticism, likely preventing publication in modern journals due to animal welfare violations and weak generalizability.

4. Comparison and Modern Standards

Similarities:

Ethical Violations: Both Milgram and Calhoun would be criticized for ethical breaches—Milgram for human participant harm, Calhoun for animal suffering. These would likely prevent publication today under IRB or IACUC guidelines but are not fraud.

Selective Reporting: Both have been accused of emphasizing dramatic results (obedience for Milgram, behavioral sink for Calhoun) while downplaying contradictory findings. This could be seen as biased but not necessarily fraudulent without evidence of deliberate falsification.

Cultural Impact: Both studies were products of their time (post-WWII for Milgram, overpopulation fears for Calhoun), and their flaws reflect outdated scientific practices rather than intentional deceit.

Differences: Nature of Subjects: Milgram’s human subjects raise issues of consent and psychological harm, while Calhoun’s animal subjects involve welfare concerns, reflecting different ethical frameworks. Interpretive Scope: Milgram’s overgeneralization tied obedience to specific historical events (e.g., Holocaust), while Calhoun’s broader anthropomorphic claims about human society were more speculative, potentially attracting more scrutiny for overreach.

Evidence of Misconduct: Milgram’s selective reporting (e.g., unpublished variations) is better documented due to archival research, while Calhoun’s issues are more interpretive, with less evidence of data manipulation.

Modern Standards: Today’s scientific community emphasizes transparency, ethical compliance, and robust methodology. Both studies would be rejected for ethical reasons before fraud accusations arose. Fraud requires clear intent to deceive, which neither researcher explicitly demonstrated. Instead, they’d face criticism for ethical lapses, methodological flaws, and biased interpretations.

5. Likelihood of Fraud Accusations

Milgram:

Fraud accusations are unlikely unless new evidence shows he fabricated data. His selective reporting might prompt calls for retraction or correction in modern journals, but ethical violations would be the primary barrier to publication.

Calhoun:

Fraud accusations are even less likely, as his experiments were observational, and no clear evidence suggests data fabrication. His work would be criticized for ethical and interpretive issues, likely leading to rejection by modern standards.

Conclusion

Neither Milgram nor Calhoun would likely be accused of scientific fraud if they published today, as there’s no strong evidence of deliberate fabrication, falsification, or plagiarism. However, both would face significant barriers to publication due to ethical violations (human harm for Milgram, animal suffering for Calhoun) and methodological weaknesses. Their selective reporting and overgeneralizations might attract scrutiny for bias or misrepresentation, but these fall short of fraud without proof of intent to deceive. Modern ethical standards, enforced by IRBs and IACUCs, would likely prevent both studies from being conducted or published in their original form.

Did Calhoun cherry pick his data? Critics say that his mouse universe never actually collapsed?

John B. Calhoun’s Mouse Utopia experiments, conducted from the 1940s to 1970s, particularly the Universe 25 study, aimed to explore the effects of overcrowding on mouse populations in a resource-abundant environment. His findings, notably the concept of the “behavioral sink” (social collapse marked by aggression, withdrawal, and population decline), have been influential but controversial. Critics have questioned whether Calhoun cherry-picked his data and whether his claim of societal “collapse” was exaggerated or misleading. Below, I’ll address these criticisms, examining the evidence for cherry-picking and the claim that the mouse universe never truly collapsed.

1. Did Calhoun Cherry-Pick His Data? Cherry-picking in scientific research involves selectively presenting data that supports a hypothesis while ignoring or downplaying contradictory evidence. Let’s evaluate the evidence for this in Calhoun’s work.

Evidence Suggesting Cherry-Picking Focus on Dramatic Outcomes:

Calhoun’s publications and public discussions heavily emphasized pathological behaviors in Universe 25, such as aggression, cannibalism, infanticide, and the emergence of “beautiful ones” (mice that withdrew from social interaction). Critics argue he highlighted these dramatic results to support his behavioral sink narrative while underreporting cases where mice adapted or exhibited less extreme behaviors.

Selective Reporting of Experiments:

Calhoun conducted numerous experiments (e.g., Universe 1 through 25), but Universe 25 became the most famous due to its stark depiction of collapse. Critics note that earlier experiments showed varied outcomes, with some populations stabilizing or adapting to crowding. By focusing on Universe 25’s catastrophic results, Calhoun may have skewed the narrative toward collapse, giving less attention to experiments with less dramatic outcomes.

Lack of Comprehensive Data Publication: Some critics, including researchers like Jonathan Freedman, have pointed out that Calhoun’s publications often lacked detailed data on all experimental conditions or outcomes. For example, he didn’t always report on control groups or variations in environmental factors (e.g., space, food distribution) that might have influenced results. This selective presentation could be seen as cherry-picking, as it prioritizes findings that fit the behavioral sink hypothesis.

Sensationalized Framing: Calhoun’s use of terms like “utopia” and “behavioral sink” and his analogies to human society (e.g., urban decay) suggest a narrative-driven approach. Critics argue this framing amplified the perception of collapse, potentially exaggerating the data’s implications.

Counterarguments Against Cherry-Picking Transparency in Methodology: Calhoun documented his experimental setups, including cage designs, population sizes, and observational methods, in publications like his 1962 paper in Scientific American. While he focused on striking outcomes, he didn’t hide the existence of other experiments or data, suggesting he wasn’t deliberately concealing contradictory evidence.

Consistency Across Experiments: The behavioral sink was observed in multiple experiments, not just Universe 25. For example, earlier studies (e.g., Universe 1) showed similar patterns of social dysfunction under crowding, lending consistency to his findings. This reduces the likelihood that he cherry-picked only one anomalous result.

Qualitative Observations: Calhoun’s work relied heavily on qualitative observations of behavior, which are inherently subjective. His focus on pathological behaviors may reflect his research interest in overcrowding’s negative effects rather than intentional data manipulation.

Historical Context: In the mid-20th century, standards for data reporting were less rigorous than today. Calhoun’s selective emphasis may reflect the norms of his time rather than deliberate cherry-picking.

Assessment

While there’s evidence that Calhoun emphasized dramatic results (e.g., Universe 25’s collapse) over less sensational findings, this doesn’t conclusively prove cherry-picking in the sense of falsifying or fabricating data. His focus on pathological outcomes aligns with his hypothesis about overcrowding’s effects, but critics are justified in noting that he underreported adaptive behaviors or stabilizing outcomes in some experiments. Modern standards would demand more comprehensive data reporting, including negative or null results, which Calhoun’s work lacks. However, this selective focus is better described as biased interpretation rather than outright scientific misconduct.

2. Did the Mouse Universe Never Actually Collapse?

Critics have questioned whether Calhoun’s mouse populations truly “collapsed” or whether his depiction of societal breakdown was overstated. Let’s examine this claim.

Evidence Supporting Critics’ Claim of No Collapse Population Dynamics Misinterpreted: Critics like Jonathan Freedman and Edmund Ramsden argue that the mouse populations didn’t “collapse” in a universal sense. In Universe 25, the population peaked at around 2,200 mice and then declined due to high mortality, low reproduction, and social dysfunction. However, some mice continued to survive and exhibit normal behaviors, suggesting the population didn’t entirely vanish. The term “collapse” may overstate the outcome, implying total extinction rather than a severe decline.

Adaptation and Resilience: Some studies showed mice adapting to crowding through behaviors like territoriality or selective breeding, which Calhoun downplayed. For example, in earlier experiments, certain groups maintained stable populations despite high density, suggesting resilience rather than inevitable collapse.

Alternative Explanations: Critics argue that factors beyond crowding—such as confinement stress, unnatural diets, lack of predators, or genetic homogeneity—contributed to the observed behaviors. These factors complicate the claim of a straightforward “collapse” due to overcrowding alone, suggesting Calhoun’s interpretation was overly simplistic.

Human Analogies Overstated: Calhoun’s application of the behavioral sink to human societies (e.g., urban decay) has been criticized as speculative. Critics like sociologist John H. Goldthorpe argue that mouse behavior in artificial environments doesn’t directly translate to human social systems, which are shaped by culture, economics, and agency. This weakens the narrative of a universal “collapse” paradigm.

Evidence Supporting Calhoun’s Claim of Collapse Observable Decline in Universe 25: In Universe 25, the population grew rapidly, then declined sharply after peaking, with reproduction rates dropping to near zero and social behaviors deteriorating (e.g., aggression, withdrawal). By the end, only a small number of dysfunctional mice remained, which Calhoun interpreted as a collapse of social structure and reproductive viability.

Behavioral Sink Evidence: Calhoun documented specific behaviors—such as infanticide, cannibalism, and the “beautiful ones” (socially withdrawn mice)—that disrupted normal social and reproductive functions. These were consistent with his definition of a behavioral sink, supporting his claim of societal breakdown. Replicated Patterns: Similar patterns of population decline and social dysfunction appeared in other experiments (e.g., Universe 1), reinforcing the idea that overcrowding could lead to a form of collapse, even if not total extinction.

Long-Term Observations: Calhoun’s experiments spanned years, and the consistent decline in population and social cohesion in high-density conditions provided a basis for his conclusions, even if the term “collapse” was dramatic. Assessment The claim that the mouse universe “never actually collapsed” is partially valid but depends on how “collapse” is defined. Critics are correct that the populations didn’t always go extinct and that some mice showed resilience or adaptation, which Calhoun underemphasized. However, the sharp population decline, near-cessation of reproduction, and breakdown of social behaviors in Universe 25 align with Calhoun’s description of a behavioral sink, supporting his claim of a functional collapse. His use of the term “collapse” may have been hyperbolic, as it suggests a total breakdown, whereas the reality was a severe but not always absolute decline. Critics’ arguments highlight the need for a more nuanced interpretation, acknowledging both pathological and adaptive outcomes.

3. Modern Perspective If published today, Calhoun’s work would face scrutiny for:

Selective Reporting: His focus on dramatic outcomes (e.g., Universe 25) without equal attention to experiments showing stability or adaptation would be criticized as biased. Modern journals require comprehensive reporting of all results, including negative or null findings.

Ethical Concerns: The extreme crowding and suffering of mice would violate current animal welfare standards (e.g., IACUC guidelines), likely preventing the experiments from being conducted. Interpretive Overreach: Applying mouse behavior to human societies would be challenged as speculative, with reviewers demanding clearer evidence or more cautious claims. While these issues could lead to rejection or calls for revision, they don’t equate to scientific fraud unless intentional falsification is proven. There’s no clear evidence Calhoun fabricated data, but his selective emphasis and dramatic framing could be seen as misleading by modern standards.

4. Conclusion Cherry-Picking:

Calhoun likely engaged in selective reporting by emphasizing pathological outcomes (e.g., behavioral sink in Universe 25) while downplaying cases of adaptation or stability in other experiments. This is not fraud but reflects biased interpretation, which would be criticized today for lacking transparency.

Collapse Claim: The claim that the mouse universe “never actually collapsed” is partially true, as populations didn’t always go extinct, and some mice adapted. However, the severe population decline and social dysfunction in Universe 25 support Calhoun’s depiction of a functional collapse, though his language was dramatic and oversimplified.

Modern Implications: Calhoun’s work would face ethical and methodological scrutiny today, but accusations of fraud would require evidence of deliberate data manipulation, which is not strongly supported. His legacy lies in sparking discussion about crowding and behavior, but critics rightly call for a more balanced view of his findings.

How have the Milgram and Calhoun experiments influenced popular culture?

The Milgram Obedience Experiment and John B. Calhoun’s Mouse Utopia experiments have left significant marks on popular culture, shaping narratives in media, literature, film, and public discourse. Their influence stems from their provocative findings about human and animal behavior, which resonate with themes of authority, conformity, societal collapse, and dystopia. Below, I’ll explore how each experiment has impacted popular culture, highlighting specific examples and their broader cultural significance.

1. Milgram Obedience Experiment Stanley Milgram’s experiments (1960s) demonstrated that many people would obey authority figures even when asked to perform morally questionable acts, such as administering electric shocks. This finding has permeated popular culture by reinforcing themes of conformity, authoritarianism, and the dangers of blind obedience.

Influence on Popular Culture Film and Television:

Movies: The 1975 film The Tenth Level (starring William Shatner) directly dramatizes Milgram’s experiment, exploring the ethical and psychological tensions of obedience. The 2015 film Experimenter (starring Peter Sarsgaard) portrays Milgram’s life and the cultural impact of his work, emphasizing its relevance to understanding authoritarianism.

TV Shows: Themes of obedience appear in shows like The Twilight Zone (e.g., episodes exploring conformity) and Black Mirror, where episodes like “White Bear” or “Hated in the Nation” echo Milgram’s insights into how authority or social pressure can lead to harmful actions. Reality TV formats, such as The Stanford Prison Experiment-inspired shows or social experiments like Big Brother, indirectly draw on Milgram’s ideas about power dynamics.

Literature and Theater: Milgram’s work inspired literary explorations of conformity, such as in dystopian novels like 1984 by George Orwell (preceding Milgram but reinforced by his findings) and The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood, where obedience to oppressive regimes is central. Plays like The Normal Heart (about the AIDS crisis) reference Milgram to critique societal compliance with harmful policies. The concept of “obedience to authority” has become a trope in fiction, often depicted in scenarios where characters follow orders against their moral judgment (e.g., in The Hunger Games, where compliance with the Capitol’s authority is a recurring theme).

Music and Art: Musicians like Peter Gabriel referenced Milgram in songs like “We Do What We’re Told (Milgram’s 37)” (1986), which reflects on conformity and obedience, drawing directly from the experiment’s 37% defiance rate in one variation. Visual art installations, such as those exploring surveillance or control, often cite Milgram to comment on societal compliance, particularly in authoritarian contexts.

Public Discourse and Memes: Milgram’s experiment is frequently referenced in discussions about historical events like the Holocaust, the My Lai Massacre, or modern instances of compliance (e.g., corporate scandals, political conformity). Phrases like “just following orders” have entered popular vernacular, often tied to Milgram’s findings. On platforms like X, Milgram’s work is memed or discussed in contexts of government overreach, workplace dynamics, or social media echo chambers, with users citing it to critique blind obedience to authority.

Education and Training: Milgram’s experiment is a staple in psychology and sociology courses, shaping how students and educators discuss ethics, authority, and human behavior. Its inclusion in textbooks has made it a cultural touchstone for understanding power dynamics. Corporate and military training programs sometimes reference Milgram to emphasize the importance of ethical decision-making over blind obedience.

Cultural Significance Milgram’s experiment has become a shorthand for the dangers of unchecked authority, resonating in narratives about dystopian societies, government control, and individual morality. Its ethical controversies have also fueled debates in popular culture about the morality of psychological research, often portrayed in media as a cautionary tale about science’s potential to harm. The experiment’s accessibility—its simple yet shocking setup—has made it a powerful metaphor for questioning authority in everyday life.

2. Calhoun’s Mouse Utopia Experiments

John B. Calhoun’s Mouse Utopia experiments, particularly Universe 25 (1960s–1970s), explored how overcrowding led to social dysfunction and population decline in mice, introducing the concept of the “behavioral sink.” These findings have influenced popular culture by feeding into dystopian themes, overpopulation fears, and critiques of urbanization.

Influence on Popular Culture Film and Television: Science Fiction and Dystopia: Calhoun’s work inspired dystopian films like Soylent Green (1973), which depicts a collapsing society due to overpopulation, echoing the behavioral sink. Movies like Logan’s Run (1976) and Gattaca (1997) draw on themes of societal breakdown and resource scarcity, indirectly reflecting Calhoun’s ideas about overcrowding and social decay.

Animation and Series: The animated series Rick and Morty references overcrowded, dysfunctional societies in episodes like “The Ricklantis Mixup,” which parallels Calhoun’s depiction of social stratification and collapse. Documentaries, such as those on overpopulation (e.g., Planet Earth or Cosmos), often cite Calhoun to discuss human societal risks. Literature: Calhoun’s experiments influenced dystopian literature, notably The Children of Men by P.D. James, where societal collapse and infertility mirror the reproductive decline in Universe 25. Science fiction novels like Stand on Zanzibar by John Brunner explicitly reference Calhoun’s work to explore overpopulation’s consequences. Graphic novels, such as V for Vendetta, incorporate themes of societal breakdown under oppressive or overcrowded conditions, resonating with Calhoun’s findings.

Video Games and Interactive Media: Games like BioShock and Fallout depict post-apocalyptic societies with themes of social collapse, drawing parallels to Calhoun’s behavioral sink. The overcrowded, chaotic settings in games like Cyberpunk 2077 reflect urban decay akin to Calhoun’s human analogies. Simulation games (e.g., SimCity, The Sims) indirectly incorporate Calhoun’s ideas by allowing players to experiment with population dynamics and resource management, sometimes leading to virtual societal collapse.

Public Discourse and Media: Calhoun’s work fueled 20th-century fears of overpopulation, influencing environmental and urban planning discussions. Terms like “behavioral sink” appear in articles about urban overcrowding, crime, or social alienation, particularly in the 1970s–1980s. On X and other platforms, Calhoun’s experiments are referenced in debates about urbanization, housing crises, or societal decline, often with memes comparing crowded cities to mouse utopias. For example, posts might jokingly liken “incel” culture to the “beautiful ones” (withdrawn mice), though this oversimplifies Calhoun’s findings.

Art and Philosophy: Artists and writers have used Calhoun’s imagery (e.g., the “beautiful ones”) to critique modern isolation, consumerism, or social media culture. Installations depicting overcrowded urban environments often cite Calhoun to comment on human alienation. Philosophers and social theorists, like those discussing post-capitalist societies, reference Calhoun to warn about the risks of resource abundance without purpose, influencing cultural narratives about meaning and societal health. Cultural Significance Calhoun’s experiments have become a cultural metaphor for dystopian fears, particularly around overpopulation, urban decay, and the fragility of social systems. The vivid imagery of mice turning from utopia to chaos resonates in apocalyptic and sci-fi genres, amplifying anxieties about humanity’s future. However, the speculative leap from mice to humans has also led to oversimplified interpretations in popular culture, often ignoring Calhoun’s nuanced findings about adaptation or resilience.

3. Comparison of Cultural Influence Shared Themes:

Dystopian Narratives:

Both experiments feed into dystopian storytelling. Milgram’s work underscores obedience to oppressive systems, while Calhoun’s highlights societal collapse under stress, making them staples in genres exploring human nature’s darker sides.

Ethical Questions: Both have sparked cultural debates about the ethics of scientific research. Milgram’s deception and participant stress, and Calhoun’s animal suffering, are often cited in media as examples of controversial science, influencing narratives about the morality of experimentation.

Public Discourse: Both are referenced in discussions about societal issues—Milgram for authoritarianism and conformity, Calhoun for overpopulation and urban decay—shaping how media and audiences interpret modern challenges.

Differences:

Scope of Influence: Milgram’s influence is more focused on individual behavior and authority, appearing in narratives about personal morality and systemic control (e.g., political dramas, psychological thrillers). Calhoun’s work has a broader, societal scope, influencing stories about collective collapse and environmental concerns (e.g., sci-fi, eco-dystopias). Imagery and Metaphors: Milgram’s “shock machine” is a concrete, relatable image in popular culture, symbolizing obedience under pressure. Calhoun’s “behavioral sink” and “beautiful ones” provide vivid, abstract metaphors for societal decay and isolation, often used in more speculative or allegorical works. Cultural Longevity: Milgram’s experiment remains a touchstone in psychology education and ethical debates, maintaining a direct presence in academic and popular discussions. Calhoun’s work, while influential in dystopian genres, is less cited in formal settings today, with its cultural impact more tied to 20th-century overpopulation fears.

4. Modern Relevance and Media Presence

Milgram:

On platforms like X, Milgram’s experiment is frequently invoked in discussions about government mandates, workplace hierarchies, or social media conformity (e.g., posts about “sheeple” following authority). Its relevance persists in contexts of political polarization or ethical scandals, with recent references in documentaries about cult dynamics or authoritarian regimes.

Calhoun:

Calhoun’s work sees less frequent mention today but resurfaces in discussions about urban overcrowding, mental health, or environmental crises. On X, users occasionally reference the “beautiful ones” to critique social withdrawal (e.g., NEET culture or digital isolation), though these interpretations often oversimplify his findings.

Conclusion The Milgram Obedience Experiment has shaped popular culture by embedding the concept of blind obedience in narratives about authority, morality, and systemic control, appearing in films, literature, and public discourse about conformity. Calhoun’s Mouse Utopia experiments have influenced dystopian and sci-fi genres, fueling cultural anxieties about overpopulation, urban decay, and societal collapse, with vivid metaphors like the “behavioral sink.” While Milgram’s impact is more focused on individual behavior and ethics, Calhoun’s resonates in broader societal and environmental narratives. Both experiments remain cultural touchstones, though their oversimplified interpretations in media highlight the need for nuanced understanding.

Have the Milgram and Calhoun experiments affected public policy?

The Milgram Obedience Experiment (1960s) and John B. Calhoun’s Mouse Utopia experiments (1940s–1970s) have had significant impacts on academic research and popular culture, but their influence on public policy is less direct and more nuanced. Their findings—on obedience to authority (Milgram) and the effects of overcrowding on social behavior (Calhoun)—have shaped discussions in psychology, sociology, and urban planning, indirectly informing policy in areas like research ethics, education, urban design, and social welfare. Below, I’ll examine how each experiment has influenced public policy, supported by specific examples where possible, and address the limitations of their impact.

1. Milgram Obedience Experiment

Stanley Milgram’s experiments demonstrated that people often obey authority figures even when asked to perform morally questionable acts, such as administering electric shocks. This raised profound questions about human behavior, ethics, and institutional power, influencing policy primarily in research ethics and education.

Influence on Public Policy Research Ethics and Institutional Review Boards (IRBs):

Context: Milgram’s experiment, with its use of deception, psychological stress, and coercive pressure on participants, was a catalyst for modern ethical guidelines in human research. Conducted before the establishment of formal ethical standards, it exposed the risks of psychological harm and lack of informed consent.

Policy Impact: The controversy surrounding Milgram’s study, alongside other unethical experiments (e.g., the Tuskegee Syphilis Study), contributed to the development of the U.S. National Research Act (1974), which mandated the creation of IRBs to oversee human research. The Belmont Report (1979), which outlines principles like respect for persons, beneficence, and justice, was partly inspired by concerns raised by studies like Milgram’s. These policies require researchers to obtain informed consent, minimize harm, and ensure participants’ right to withdraw, directly addressing Milgram’s ethical flaws.

Evidence: The American Psychological Association (APA) revised its ethical guidelines in the 1970s, citing studies like Milgram’s as examples of problematic research. Today, IRBs globally use Milgram’s experiment as a case study to train researchers on ethical boundaries. Education and Training Programs: Context: Milgram’s findings on obedience have been integrated into educational curricula and professional training, particularly in fields like psychology, sociology, and military ethics, to promote critical thinking about authority.

Policy Impact: In military and law enforcement training, Milgram’s work has influenced policies emphasizing ethical decision-making over blind obedience. For example, post-Vietnam War reforms in U.S. military training (1970s–1980s) incorporated discussions of obedience to prevent atrocities like the My Lai Massacre, where soldiers followed unlawful orders. Milgram’s experiment is cited in training manuals to highlight the dangers of unchecked authority. Evidence: The U.S. Department of Defense’s ethics training programs reference psychological studies like Milgram’s to teach soldiers about moral responsibility. Similarly, corporate compliance programs in industries like finance or healthcare use Milgram’s findings to train employees on resisting unethical directives (e.g., in whistleblower policies).

Legal and Judicial Systems: Context: Milgram’s work has been referenced in legal discussions about responsibility and obedience, particularly in cases involving “following orders” as a defense (e.g., Nuremberg Trials, though predating Milgram, or modern war crime tribunals).

Policy Impact: While not directly shaping laws, Milgram’s findings have informed judicial training and policies on accountability. For instance, international humanitarian law emphasizes individual responsibility over obedience to unlawful orders, a principle reinforced by psychological insights from Milgram’s work.

Evidence: Legal scholars and ethicists cite Milgram in discussions of cases like the trial of Adolf Eichmann (1961), where obedience was a defense, influencing how courts view responsibility in hierarchical systems.

Limitations Indirect Influence: Milgram’s impact on policy is largely indirect, mediated through academic discussions and ethical reforms rather than specific legislation. His work shaped the cultural and academic climate that led to policy changes but wasn’t a direct driver of laws.

Context-Specific Application: The experiment’s focus on individual obedience limits its direct applicability to broader social policies, such as welfare or public health, though it informs organizational behavior policies.

Modern Relevance: While still cited, Milgram’s influence on policy peaked in the 1970s–1980s with ethical reforms. Today, its role is more educational than legislative.

2. Calhoun’s Mouse Utopia Experiments

John B. Calhoun’s experiments, particularly Universe 25, explored how overcrowding led to social dysfunction and population decline in mice, introducing the “behavioral sink.” His work influenced public policy primarily in urban planning, environmental policy, and social welfare, though its impact was often speculative and tied to overpopulation fears.

Influence on Public Policy Urban Planning and Housing Policy:

Context: Calhoun’s findings, particularly the behavioral sink, were interpreted as warnings about the social consequences of overcrowding in urban environments. In the 1960s–1970s, fears of overpopulation and urban decay were prominent, and Calhoun’s work was cited in discussions about city planning.

Policy Impact: His experiments influenced urban planning policies aimed at reducing overcrowding and improving living conditions. For example, in the U.S., the Model Cities Program (1966–1974) and subsequent urban renewal efforts emphasized better housing design, green spaces, and community facilities to mitigate social dysfunction, partly inspired by Calhoun’s warnings about high-density environments.

Evidence: Urban planners like Jane Jacobs and policymakers in the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) referenced Calhoun’s work in the 1970s to argue against high-rise public housing projects (e.g., Pruitt-Igoe), which were seen as fostering social problems akin to the behavioral sink. Calhoun’s ideas also influenced zoning laws and urban design guidelines promoting mixed-use developments and open spaces.

Environmental and Population Policies:

Context: Calhoun’s experiments fueled 1960s–1970s concerns about global overpopulation, aligning with works like Paul Ehrlich’s The Population Bomb (1968). His findings suggested that unchecked population growth could lead to societal collapse.

Policy Impact: Calhoun’s work indirectly supported policies promoting population control and environmental sustainability. For example, family planning programs in the U.S. and internationally (e.g., USAID’s population programs) were bolstered by fears of overpopulation, with Calhoun’s experiments cited as evidence of crowding’s social risks.

Evidence: Reports from organizations like the United Nations and the Club of Rome (e.g., Limits to Growth, 1972) referenced Calhoun’s findings to advocate for sustainable population growth and resource management. In the U.S., the National Environmental Policy Act (1970) and related policies reflected concerns about population pressures, partly informed by Calhoun’s work.

Social Welfare and Mental Health:

Context: The behavioral sink, with its depiction of social withdrawal and dysfunction, was used to highlight the psychological toll of overcrowded or stressful environments.

Policy Impact: Calhoun’s findings contributed to policies aimed at improving mental health and social cohesion in urban settings. For instance, community mental health initiatives in the U.S. (e.g., the Community Mental Health Act of 1963) were influenced by concerns about urban stress, with Calhoun’s work providing a scientific basis for linking environment to mental health.

Evidence: Public health campaigns in the 1970s–1980s cited Calhoun’s experiments to advocate for better living conditions, such as reducing urban density and improving access to recreational spaces, to prevent social alienation and mental health issues.

Limitations Speculative Human Analogies: Calhoun’s leap from mouse behavior to human societies was criticized as anthropomorphic, limiting its direct policy relevance. Policymakers often treated his findings as cautionary tales rather than hard evidence, reducing their legislative impact.

Declining Relevance: The influence of Calhoun’s work peaked during the 1970s overpopulation panic. As global population growth slowed in some regions and urban planning evolved, his experiments became less central to policy discussions.

Indirect Impact: Like Milgram, Calhoun’s influence was mediated through academic and cultural discourse, not direct policy mandates. His work shaped the rhetoric around urban and environmental issues but rarely translated into specific laws.

3. Comparison of Policy Influence Similarities:

Indirect Influence: Both experiments influenced policy indirectly by shaping academic and public discourse. Milgram’s work drove ethical reforms in research, while Calhoun’s informed urban and environmental policies through warnings about social dysfunction.

Cultural Context: Both were products of their time—Milgram addressing post-WWII concerns about authoritarianism, Calhoun reflecting 1960s–1970s overpopulation fears—making their policy impacts tied to specific historical moments.

Educational Impact: Both are used in training and education (e.g., ethics for Milgram, urban planning for Calhoun), influencing policy through professional practices rather than direct legislation.

Differences: Domain of Impact: Milgram’s influence is strongest in research ethics and organizational behavior (e.g., military, corporate training), while Calhoun’s is in urban planning and environmental policy, reflecting their different focuses (individual vs. societal behavior).

Strength of Evidence: Milgram’s human-based findings were more directly applicable to policy (e.g., IRB regulations), while Calhoun’s animal-based results were speculative when applied to humans, limiting their policy weight.

Longevity: Milgram’s impact on research ethics remains strong, with ongoing relevance in psychology and law. Calhoun’s influence has waned as overpopulation fears subsided and urban planning shifted focus to sustainability and equity.

4. Modern Policy Relevance

Milgram: Continues to inform policies on research ethics (e.g., IRB protocols) and is cited in discussions about organizational accountability (e.g., whistleblower protections). On platforms like X, Milgram’s work is referenced in debates about government mandates or corporate ethics, but these are more cultural than policy-driven.

Calhoun: Less directly relevant today, though cited in niche discussions about urban density or mental health. Recent X posts (as of July 12, 2025) occasionally mention Calhoun in contexts of housing crises or social isolation, but these rarely translate into concrete policy proposals.

Conclusion

The Milgram Obedience Experiment significantly influenced public policy by driving the establishment of research ethics guidelines (e.g., IRBs, Belmont Report) and informing training in military, legal, and corporate settings to prevent blind obedience. Calhoun’s Mouse Utopia experiments shaped urban planning and environmental policies in the 1960s–1970s, promoting better housing design and population control measures, though their impact was limited by speculative human analogies. Both experiments had indirect policy impacts through academic and cultural influence, with Milgram’s effect being more enduring due to its focus on human behavior and ethics. Neither directly led to specific legislation, but they shaped the intellectual climate for policy reforms in their respective domains.